The Triangle Trade in New England and Bristol, RI

Between 1620 and 1640, approximately 20,000 English colonists came to the New England region

1. Engraving of King Philip (Metacom) by Benjamin Church, 1881; Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

As children, we learned how Squanto, or Tisquantum, a member of the Pokanoket tribe, taught the Pilgrims to plant corn, fish and hunt. We may not have been told that Squanto could communicate with the Pilgrims because in 1614 he was captured, enslaved, brought to Spain and England, and eventually returned to North America and his tribe, fluent in English. His enslavement helped him escape the smallpox pandemic that killed so many of his people. 1614 is not a year we generally equate with slavery.

2. Nathaniel Byfield, town proprietor; Courtesy of Wikipedia.

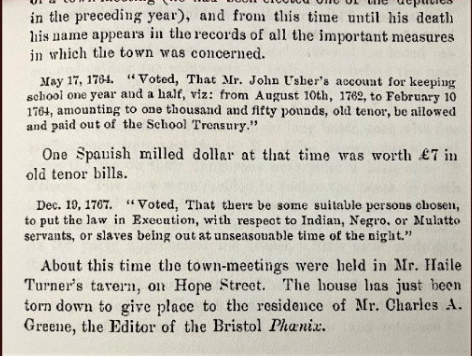

3. December 19, 1767, town vote to “monitor Indian, Negro or mulatto servants or slaves being out at unreasonable times of the night”.

In 1638, the ship “Desire” took captive Native Americans to the West Indies for sale as slaves. By 1641, the Massachusetts Bay Colony had given legal recognition to the institution of slavery.

Slavery was a cruel and profitable business. Between 1705 and 1807, 934 slave voyages from Rhode Island transported over 100,000 enslaved Africans to the West Indies and North America. 672 of those voyages originated in Newport; 167 in Bristol, 71 in Providence.

Its “Bodies of Liberties” permitted the enslavement of “lawful captives taken in just warres, or such strangers as willingly sell themselves or are sold to us.” By 1652, Rhode Island attempted to ban perpetual slavery; upon 10 years of service, or on your 24th birthday, your enslavement was to end. The law was largely ignored.

4. Charles Church inventory containing reference to: ”Negro woman and Primus”, 1746; Town of Bristol Archives.

5. Excerpt mentioning enslaved people in Bristol from The Bristol Phoenix, October 5, 1872.

On the eve of the American Revolution, Bristol was home to 132 enslaved people (115 of African descent, 17 of native descent), which represented 11% of the town’s population. Five of them, Plato Van Doorn, Thomas Lefavour, Prince Ingraham, Frank Bourne, and Juba Smith, fought with the First Rhode Island Regiment in the American Revolution.

After the Revolution, Bristol’s elite families embarked on an intensely profitable period of human trafficking. Most famous among them were the DeWolfs, but other families, including the Wilsons, Fales, Ushers, Wardwells, and Munros, also participated in the slave trade and in the manufacture of slave-related goods. Bristol remained a central hub of such activities long after the 1807 embargo outlawed the trade in enslaved peoples.

6. Illustration of the Triangle Trade; Courtesy of National Geographic. 8. 18th century sailing ship; Courtesy of Wikipedia.

7. Ship hold illustration; Courtesy of the Slave Trade Curriculum, nps.gov/timu/learn/education.

8. 18th century sailing ship; Courtesy of Wikipedia.

By 1830, Bristol’s African-American and Indigenous community had found a home in New Goree, located on Wood Street between State Street and Bay View Avenue. Many continued to work in the homes of Bristol’s elite families in relationships that paralleled the era of enslavement.

Others found work in the developing rubber industry. However, many of Bristol’s African-American families began to move elsewhere. By 1920, with only a handful of such families remaining, Bristol had largely forgotten this important part of its history.

9. George DeWolf Home, built 1810, now Linden Place; Photo courtesy of Linden Place Museum.

11. Rhode Island Slave History Medallion; Photo courtesy of Linden Place Museum.